Manipulating Exhaust and Skirting the Rules: What is Red Bull's 'Barely Legal' F1 Aerodynamic Revolution?

The dominance of Oracle Red Bull Racing in the 2023 F1 season is still fresh in our memories. Max Verstappen clinched the Drivers’ Title with 19 wins out of 22 races, and the team recorded 21 victories, shining as the Constructors’ Champions. This performance can certainly be described as ‘overwhelming dominance’ of the season, but it wasn’t the first time Oracle Red Bull Racing had such a commanding presence. That was back in 2010, with Sebastian Vettel behind the wheel of the RB6.

In our previous article, we reviewed the history of flexible wing regulations in F1, starting with the aerodynamic regulation changes that were applied after the 2025 Spanish GP. The background of these aerodynamic regulations is heavily influenced by a technical controversy that once shook the foundation of the F1 world. This is the ‘blown diffuser’ issue. From the late 2000s to the early 2010s, this technology, which dramatically improved aerodynamic performance by utilizing exhaust flow, symbolized the dispute over the interpretation of the ‘wording’ and ‘spirit’ of the regulations.

Related article: The History of ‘Legal Cheating’ in F1 – The Endless Battle of Geniuses Over the Loopholes in the Rulebook

Aerodynamic Control Through Exhaust – The Design Philosophy Pioneered by Red Bull and Renault in F1

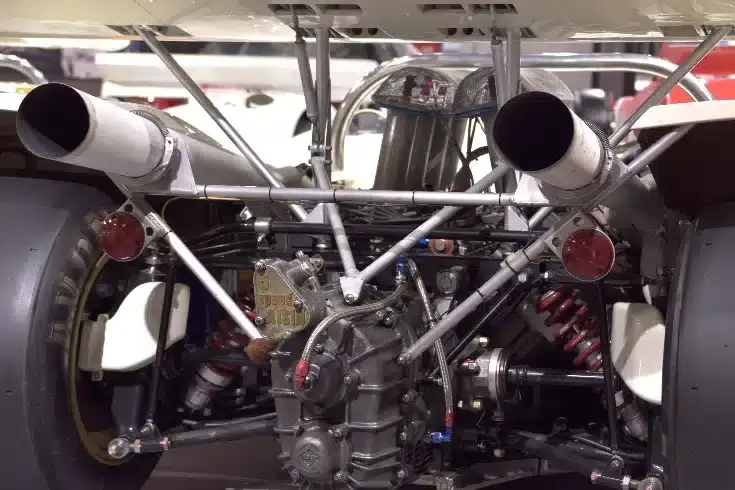

In 2010, Red Bull Racing (now Oracle Red Bull Racing) fully implemented the ‘blown diffuser’ on their RB6. This technique involves actively blowing exhaust gases into the diffuser’s airflow to increase the velocity of the air beneath the car body, artificially enhancing downforce and stabilizing maneuvers such as cornering.

Particularly noteworthy is the early adoption of the ‘Off-Throttle Blown Diffuser.’ Exhaust gases are not produced when the accelerator is not engaged, but this technology allows for the continuation of exhaust flow even when the driver releases the accelerator, by adjusting fuel injection and ignition timing. This means that the car’s stability is significantly improved at all times, giving the team a dominant advantage over their competitors.

Armed with this technology, the RB6 demonstrated exceptional competitiveness throughout the 2010 season. It secured pole position in 15 out of 19 races and achieved a total of 9 victories between Sebastian Vettel and Mark Webber. The car showed unparalleled speed, especially in medium and low-speed corners where aerodynamic performance is crucial, and in combination with the flexible wings we introduced previously, the car’s behavior was described as ‘sticking to the ground.’

As a result, Red Bull won their first Constructors’ Championship since the team’s inception, and Vettel clinched his first Drivers’ Championship with a comeback victory at the final race in Abu Dhabi.

The Issues with the Blown Diffuser

Naturally, rival teams began to question the overwhelming dominance of the RB6, raising concerns that the use of the blown diffuser might be in violation of the technical regulations.

The crux of the issue lies in the prohibition of “movable aerodynamic devices” as stipulated in Chapter 3 of the F1 Technical Regulations (Article 3.15).

*With the exception of the parts described in Articles 3.16, 3.17, and 3.18, any specific part of the car influencing its aerodynamic performance must comply with the rules relating to bodywork and be rigidly secured to the entirely sprung part of the car (rigidly secured means not having any degree of freedom).*

*With the exception of the DRS under Article 3.18, any such device must remain immobile in relation to the sprung part of the car.*

Article 3.15 (2010 Formula One Technical Regulations)

Based on this article, the FIA had restricted the use of movable elements such as wings, but exhaust gases themselves were not interpreted as a “device.” This was the technical basis that deemed the blown diffuser “legal.”

Red Bull Racing exploited this regulatory loophole regarding “static structures” and introduced an innovative method of using the “dynamic fluid” of exhaust gases to alter aerodynamic performance. Furthermore, they developed control technology that continued fuel injection and ignition even when the throttle was off, ensuring that exhaust gases were constantly fed to the diffuser even during deceleration, thereby achieving unprecedented behavior in maximizing downforce at all times.

FIA’s Shaky Response—The Recognition of “Spiritual Violation” Under Technical Directive TD011/11

However, in 2011, the FIA suddenly determined that this technique was contrary to the “spirit of the regulations” under Article 3.15 of the Technical Regulations, despite the absence of any explicit prohibition. The FIA expressed the following view:

The use of engine maps which result in the exhaust gases being blown primarily for aerodynamic effect when the driver is off-throttle is to be considered contrary to the spirit of the regulations.

Technical Directive TD011/11

In other words, even if structurally not in violation of the rules, the act of influencing aerodynamic performance through behavior (engine mapping) when the driver is not applying the throttle was deemed a violation under a new interpretation.

However, since this was not a codified rule but a technical directive issued mid-season, teams strongly objected, claiming it to be an arbitrary judgment. Renault, in particular, which supplied engines, argued that a certain amount of exhaust flow was essential for engine cooling and lubrication maintenance, and the FIA partially acknowledged this, setting a special exception.

As a result, at the Silverstone GP, a “limited blow” was permitted exclusively for Renault engines, leading to a distorted situation where the regulatory content changed during the race weekend, casting a significant shadow over the trust between the FIA and the teams.

The Codification of F1’s “Exhaust Restrictions” — The Radical Regulation Overhaul of 2012

In response to such confusion, the FIA implemented a fundamental revision of Chapter 5 (Exhaust Systems) of the Technical Regulations in 2012, introducing strict limitations on the position and orientation of the exhaust tailpipes. Here are the main provisions:

The final 100mm of the tailpipe must be located between 250mm and 600mm above the reference plane and be directed rearwards and upwards.

The tailpipe must not be angled such that any exhaust gas flow is directed at the floor or diffuser.

Article 5.8.4 (2012 Formula One Technical Regulations)

The last 100mm of the tailpipe must be positioned between 250mm and 600mm above the reference plane and must be installed to face rearward and upward.

The angle of the tailpipe must not be such that the flow of exhaust gas is directed towards the floor or diffuser.

These provisions clearly prohibited the flow of exhaust gases towards the diffuser, rendering the blown diffuser technically unfeasible.

Furthermore, the introduction of a standardized ECU (SECU) produced by McLaren Electronics to all teams mandated linearity between throttle opening and torque supply, effectively sealing off aerodynamic manipulation through engine mapping.

And in 2025—Vigilance Against ‘Techniques to Appear Legal’

While the Brown Diffuser concept has vanished from the public eye, its design philosophy seems to still be alive in the current issues surrounding flexible wings. Structures that are deemed legal in static tests selectively deform during actual driving to optimize aerodynamic performance. This behavior is fundamentally based on the same idea as the past aerodynamic control using exhaust flow.

Even in the 2025 technical regulations, Article 3.15 continues to demand the ‘rigidity’ of aerodynamic devices, but its interpretation has been further expanded.

With the exception of DRS and parts specified in Articles 3.17 and 3.18, any component influencing aerodynamic performance must remain immobile and may not rely on flexibility, flow direction, or conditional behavior to change aerodynamic personalityistics.

Article 3.15 (2025 Formula One Technical Regulations)

Excluding the Drag Reduction System (DRS) and parts specified in Articles 3.17 and 3.18, all components that influence aerodynamic performance must not move. Furthermore, mechanisms that change aerodynamic personalityistics based on flexibility, the direction of airflow, or specific conditions are also prohibited.

Thus, the evolution of the regulations towards considering even flexibility and conditional behavior as illegal demonstrates that the lessons from the Brown Diffuser have been firmly embedded in the current regulatory framework.

The Art of ‘Legal Cheating’ in High-Stakes Negotiations

The controversy surrounding the Brown Diffuser became a pivotal event in Formula 1, fundamentally questioning “what rules are.” It was not merely a battle over technological development but also an extremely sophisticated legal and strategic maneuvering involving the handling of the gray area between the “wording” and “operation” of technical regulations.

Now, in 2025, the enhanced regulations on flexible wings are a continuation of this lineage. Behind the multi-layered monitoring system, which includes static inspections, dynamic load tests, in-motion behavior surveillance by cameras, and random parc fermé inspections, lies the memory of a strategic battle with Red Bull, who once “legally cheated” using the invisible medium of exhaust.

Related article: F1 Legal Lab

Guidance on Measures by Our Firm

Monolith Law Office is a law firm with high expertise in both IT, particularly internet, and legal matters. Our firm provides support in human resources and labor management, as well as drafting and reviewing contracts for various cases, serving clients ranging from Tokyo Stock Exchange Prime-listed companies to venture businesses. For more details, please refer to the article below.

Areas of Practice at Monolith Law Office: Corporate Legal Services for IT & Startups

Category: General Corporate