Does Generating 'Voices' with AI Constitute Copyright Infringement? —Part 1: Development and Training Phase

With advances in generative AI, it has become easy to train systems on the voices of real singers and voice actors and to generate similar “voices.” In business, this capability is already used in app development, game creation, and anime production, where AI can learn human voices and create new ones.

Having generative AI learn and create new ‘voices’ based on those of existing singers and voice actors could potentially constitute copyright infringement or other illegal activities under Japanese law.

In reality, there is currently no clear interpretation regarding these issues. What exactly are the legal rights associated with a ‘voice,’ and under what circumstances could it become a problem under the Japanese Copyright Act?

At present, there is no clear, settled interpretation of these issues. It is therefore important to ask what legal rights may attach to a “voice,” and in what circumstances problems arise under Japan’s Copyright Act of Japan and related laws.

This series addresses those questions using concrete usage patterns over two parts; this first part focuses on possible rights infringements at the development and training stage of generative AI, and the second part discusses legal issues at the generation and utilization stage.

Three Legal Rights Surrounding a Person’s “Voice” Under Japanese Law

To understand what legal rights may attach to a person’s “voice,” it is useful to distinguish two aspects:

- What the voice is saying (the verbal content).

- How the voice sounds when speaking (the sonic characteristics).

In other words, the first point concerns the “content” of the voice, while the second point relates to the “sound” of the voice.

For example, if two different voice actors perform the same line “Good morning,” the content in the first case remains the same, but the sound in the second case differs.

On this basis, under current Japanese law, there are three legal rights may arise in relation to a person’s “voice”:

| ① Copyright | May arise from the voice’s content. |

| ② Neighboring Rights (limited to the rights of performers) | May arise from both the voice’s “content” and sound. |

| ③ Publicity Rights | May arise from the voice’s sound. |

About Copyrights Under Japanese Law

Copyright may arise where the content of a voice qualifies as a “work” protected under the Copyright Act of Japan. For example, when someone reads aloud a famous novel, the voice recording may fall within the scope of copyright protection, but the copyright holder is the author of the novel, not the person whose voice is heard.

Accordingly, if generative AI is used to create synthesized speech that reads the text of a famous novel, this use may infringe the copyright of the author of that novel. By contrast, if the vocal content consists of ordinary, commonplace conversation between non-famous individuals, copyright does not arise in that content because such everyday conversation does not meet the threshold of a “work” and is not protected by copyright law.

About Neighboring Rights Under Japanese Law

may arise where the vocal content is itself a work and the voice is expressed through a mode such as reading aloud. In the reading example mentioned above, the act of reading constitutes a “performance,” so neighboring rights may arise in favor of the person who performs the reading.

Unlike copyright in the underlying novel, these neighboring rights belong not to the author but to the reader who actually vocalizes the work. When dealing with human voices, it is therefore necessary to consider not only copyright in any underlying work, but also neighboring rights in the performance.

Understanding Publicity Rights in Japan

Publicity rights, as recognized by Japanese case law (Supreme Court decision of February 2, 2012, the so-called Pink Lady case), are defined as the exclusive right to exploit the customer-attracting power of a person’s name, likeness, and similar personal attributes. The Supreme Court identified the following three modes of infringing use of such attributes:

| ▶︎ Supreme Court decision on February 2, 2012 (H24.2.2) (The Pink Lady Case) ■ Key Points of the Decision ① The use of a name, likeness, etc., as an object of appreciation in itself, as in goods, ② The attachment of a name, likeness, etc., to goods with the purpose of differentiating the goods, ③ The use of a name, likeness, etc., as advertising for goods, where the sole purpose is to exploit the customer-attracting power of the name, likeness, etc., constitutes an infringement of publicity rights and is illegal under tort law. ■ Commentary by the Investigating Officer (Supreme Court Case Commentary, Civil Matters, 2012 (H24) Volume 1, page 18) The term “likeness, etc.” in the three categories of this decision refers to personal identification information of the individual, which includes, for example, signatures, autographs, voices, pen names, stage names, etc. |

In the commentary by the Investigating Officer to this decision, the expression “likeness, etc.” is interpreted as referring to personal identification information, including signatures, autographs, voices, pen names, stage names, and similar indicia. Based on the Pink Lady case, there is room for publicity rights to arise in a person’s voice itself; where the voice is identified as that of a person with customer-attracting power—such as a well-known voice actor, actor, or singer—publicity rights may arise regardless of the content of what is said, and use of that voice in any of the three modes above can constitute an infringement of publicity rights.

Three Usage Patterns in the Development and Learning Phase

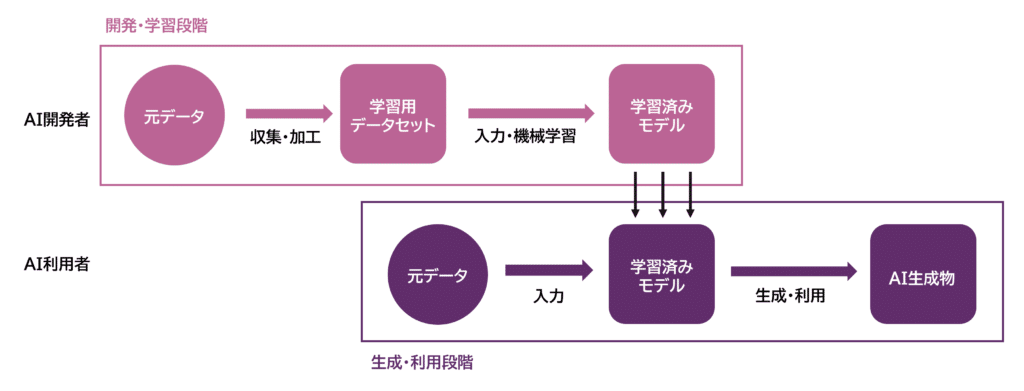

The expression “generating voices with generative AI” appears simple, but in practice the process can be divided into two stages:

- Development and learning phase.

- Generation and utilization phase.

When visualized, these processes are as follows:

Typically, AI developers carry out the first (development and learning), while AI users engage in the second (generation and utilization). Conceptually, during the development and learning phase, developers collect and accumulate original human voice data as training data, construct a training dataset, and feed that dataset into the AI to perform machine learning and create a trained model.

In the generation and utilization phase, users input new “source” data into the trained generative AI in order to generate and use AI-generated outputs. As typical usage patterns during the development and learning phase, the following three patterns can be envisaged:

- Pattern 1: Collecting, accumulating, processing, and using human voice data as training data for AI development

- Pattern 2: Selling or publishing the training datasets used in AI development

- Pattern 3: Selling or publishing the generative AI itself

The sections below briefly explain what kinds of rights infringements can potentially arise in each of these patterns.

Pattern 1: Collecting, Storing, Processing, and Utilizing Human Voice Data for AI Development

Pattern 1 focuses on the stage of collecting, storing, processing, and then using human voice data as training data in order to train the AI.

Relation to Copyright Law

In more concrete terms, the use of human voice data in Pattern 1 corresponds to the act of developing the generative AI itself. Under Japan’s Copyright Act of Japan, AI development falls within “information analysis” as defined in article 30-4, paragraph 2, so, in principle, acts of using copyrighted works to the extent necessary for such development do not constitute copyright infringement (art. 30-4).

However, there is a major exception to this rule. If, in creating the training dataset, the purpose is to generate AI outputs that embody the essential expressive characteristics of the original data (an “expression output purpose”), article 30-4 does not apply and the use becomes unlawful. For example, if the voice data of other voice actors are used with the aim of reproducing or paying homage to the distinctive voice of a particular voice actor, that use may be considered to have an expression output purpose and could constitute copyright infringement.

Relation to Neighboring Rights

With respect to neighboring rights, article 102 of the Copyright Act of Japan provides that article 30-4 applies mutatis mutandis to neighboring rights. Accordingly, as a rule, performing or otherwise engaging in expressive acts for the purpose of developing generative AI does not constitute an infringement of neighboring rights.

Relation to Publicity Rights

Publicity rights become a concern in Pattern 1 where the development of generative AI is aimed at creating the “voice” of a specific, well-known individual with customer-attracting power. In assessing whether such development constitutes infringement of publicity rights, the three modes of infringing conduct identified in the Pink Lady case serve as reference points.

First, the mere act of developing generative AI with the aim of generating the “voice” of a specific celebrity does not fall within the three infringement modes identified by the Supreme Court. However, if the development is considered to be “solely aimed at utilizing the customer-attracting power of names, likenesses, and so on,” it may qualify as an infringement of publicity rights and thus a tortious act.

For customer-attracting use to arise, third-party customers must perceive, during the AI development stage—particularly when the training dataset is created—that the voice in question is that of the celebrity concerned. If customers do not perceive this, customer attraction cannot occur in the first place; moreover, at the development stage of generative AI, it is ordinarily difficult to conceive of any involvement by third-party customers. Accordingly, there is very little room for uses in Pattern 1 to be treated as infringements of publicity rights.

Pattern 2: Sale and Publication of Training Datasets Used in AI Development

Pattern 2 concerns potential rights infringements that may arise when training datasets used for AI development are sold or made publicly available.

Relation to Copyright

If original data are stored in a training dataset either in their original form or with only minor processing, the sale or publication of that dataset may constitute infringement of the transfer right (art. 26-2) or public transmission right (art. 23) in respect of the copyrighted work or any derivative work (art. 28). Therefore, selling or publishing such a dataset without the consent of the copyright holder amounts to copyright infringement.

However, article 30-4 provides that, where use is “for the purpose of information analysis,” copyrighted works may be used “by any means and to the extent deemed necessary.” Consequently, where transfer or publication of the dataset is carried out for the development of generative AI and remains within the necessary limits for information analysis, it does not constitute copyright infringement.

Relation to Neighboring Rights

Similarly, by virtue of article 102 of the Copyright Act of Japan, article 30-4 applies mutatis mutandis to neighboring rights. As a general rule, therefore, selling or publishing training datasets for the development of generative AI does not constitute infringement of neighboring rights.

Relation to Publicity Rights

Some training datasets store the voices of particular celebrities in a format that allows playback in their original form. Nonetheless, such datasets are typically used only for the development of generative AI and do not fall within the category of “using names, likenesses, and so on as products or the like whose object is their appreciation in themselves,” as described in the Pink Lady decision.

Therefore, it can be said that there is little room for the act of using such datasets to infringe upon publicity rights.

Pattern 3: Sale and Publication of the AI Itself

Pattern 3 addresses potential rights infringements at the stage where the trained AI model itself (the generative AI) is sold or made publicly available.

Relation to Copyright

Unlike training datasets, the trained AI model does not, in principle, retain any parts of the original data (copyrighted works) that embody creative expression. The generative AI itself—namely, the trained model—therefore cannot be regarded as a derivative work of the original data, and the publication or sale of the AI does not constitute copyright infringement.

Relation to Neighboring Rights

For the same reason, it is not conceivable that any part of the original data possessing creative expression remains in the trained model. Accordingly, the sale or publication of the generative AI itself does not infringe neighboring rights.

Relation to Publicity Rights

Even an AI capable of generating, freely and with high precision, the voice of a specific celebrity does not fall squarely within any of the three modes of infringing conduct identified by the Supreme Court in the Pink Lady case. However, in practice, such AI systems are usually marketed on the value that they can generate the specific celebrity’s voice freely and with high precision, and customers typically purchase them for that reason.

In this sense, the sale of such AI may be regarded as conduct similar to one of the three infringing modes recognized in the Pink Lady decision and is therefore highly likely to constitute infringement of publicity rights.

Conclusion: Consult Experts on the Relationship Between Generative AI and Copyright

This article has explained the legal rights that may arise in relation to human voices, and the types of problematic conduct that may occur when those voices are used, with reference to concrete examples. When considering legal rights in human voices, it is important to separate content and sound, and to recognize the potential applicability of copyright, neighboring rights, and publicity rights.

This first part has focused on the development and learning stage of generative AI, while the second part considers legal issues at the generation and utilization stage. Given the complexity and the current lack of clear interpretive consensus, companies and developers should seek expert advice on how generative AI interacts with copyright, neighboring rights, and publicity rights under Japanese law.

Related article: Could Generating Voices with AI Lead to Copyright Infringement? (#2 Generative & Utilization Stages)

Guidance on Measures Provided by Our Firm

Monolith Law Office is a law firm with extensive experience in both IT, particularly the internet, and legal matters. In recent years, generative AI and intellectual property rights surrounding copyright have garnered significant attention, and the necessity for legal checks has been increasingly on the rise. Our firm provides solutions related to intellectual property, which are detailed in the article below.

Areas of practice at Monolith Law Office: IT & Intellectual Property Legal Services for Various Companies

Category: IT